By The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives – Saskatchewan Office.

Introduction

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives – Saskatchewan Office welcomes the opportunity to present our views and recommendations to SaskForward. The CCPA is Canada’s leading progressive think tank with offices in Ontario, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Nova Scotia. The CCPA is a registered non-profit charity. We depend on the generosity of our more than 12,000 individual supporters across Canada.

Our submission focuses on one broad transformational change that the Saskatchewan government could adopt immediately that would have wide-ranging impacts for the provision and delivery of services and programs throughout the province. Put simply, our recommendation is for the government to rescind its announced austerity measures and resist further spending cuts in favour of expanded public expenditures during this period of economic downturn. The instinct of governments across the political spectrum when faced with economic contraction has been to cut public spending as a means to reduce deficits and restore growth. This instinct is certainly shared by the Saskatchewan government, which has recently announced large spending cuts in health ($63.9 million), education ($8.7 million) and social services ($9.2 million). This is in addition to funding and program cuts announced in the 2016 budget which saw cuts to Seniors and Children’s Drug Plans, reduced funding for the Alternative Measures and Aboriginal Courtworker Program, elimination of funds for urban parks and claw-backs to some social assistance programs.

Unfortunately, this instinct to cut during an economic downturn is counter-productive to restoring growth and may result in a protracted economic slump. As this submission will demonstrate, the adoption of austerity measures during an economic downturn can have the perverse effect of prolonging economic stagnation, driving up unemployment, increasing deficits and debt and hindering the growth of the economy.

Assessing Austerity

Due to the boom in commodity prices, Saskatchewan was able to weather much of the economic recession that beset the rest of the world since the financial crisis of 2008. It is only with the recent downturn in commodity prices – particularly oil – that Saskatchewan is beginning to feel the symptoms of economic stagnation that have plagued other regions. The silver-lining is we have a wealth of recent examples from around the world to assess which policies can best combat an economic downturn and return us to more robust growth.

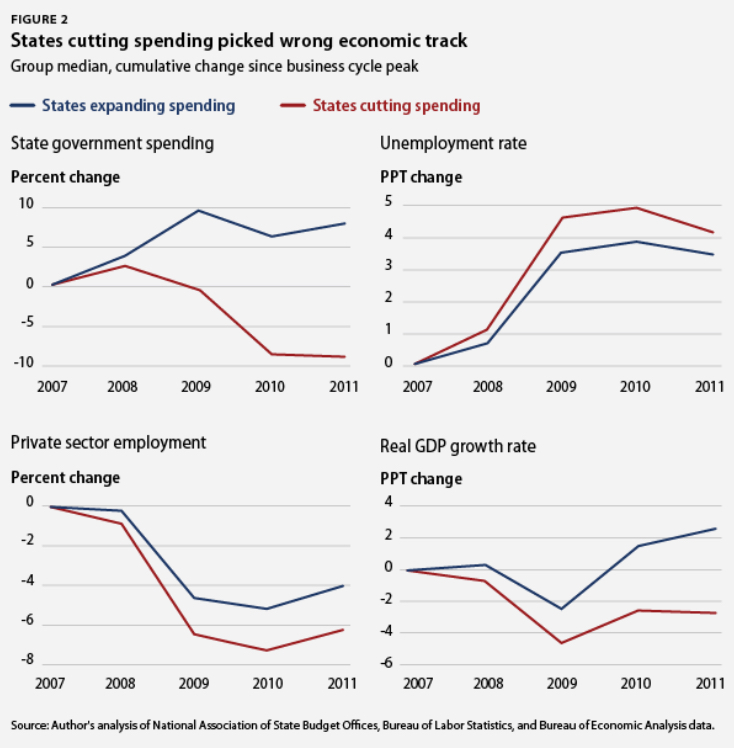

The United States can act as a particularly useful laboratory to assess the efficacy of austerity, as state-level governments addressed the economic recession in divergent ways. As Adam Hersh notes, since the start of the Great Recession, twenty U.S. states adopted varying degrees of public spending reductions as the best means to address the downturn, while thirty states adopted varying degrees of expanded public spending. Surveying the results of these divergent responses to the economic recession in the United States, we see that states that adopted an expansionary fiscal policy were able to pull themselves out of recession sooner, while experiencing less of the negative economic impacts of the recession. Overall, states cutting spending cut expenditures on public services and investments by an average of 9.1 percent over the course of the recession and recovery, from 2007 through 2011. States that expanded expenditures did so by an average of 8 percent. As the chart below illustrates, states that adopted an expansionary fiscal policy experienced less unemployment, higher private sector employment growth and significant growth to GDP in comparison to those states that adopted wide-spread spending cuts. Indeed, the greatest divergence between states was in economic growth. Expanding states accelerated well ahead of their prerecession growth rates while cutting states languished with growth much slower than before the recession. At the worst of the recession in 2009, GDP growth in expenditure-expanding states was on average 2.4 percentage points below the prerecession pace of growth. Expenditure-cutting states fell much deeper into the recession hole, with their GDP growth rates on average falling 4.6 percentage points below their prerecession level.

Enacting a Vicious Circle

The negative experience of these states that adopted austerity should not come as a surprise. Despite the prevailing economic orthodoxy that austerity measures can restore growth during an economic downturn, actual empirical evidence of this occurring is in very short supply. Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – once a champion of fiscal austerity – has been forced to admit this. Assessing 30 years of evidence, the IMF unequivocally concludes: “In economists’ jargon, fiscal consolidations [austerity] are contractionary, not expansionary. This conclusion reverses earlier suggestions in the literature that cutting the budget deficit can spur growth in the short term.”

Moreover, the IMF demonstrates that adoption of austerity measures during an economic downturn is “likely to lower incomes—hitting wage-earners more than others—and raise unemployment, particularly long-term unemployment.” Such effects will have the consequence of exacerbating deficits as falling incomes diminish government tax receipts while growing unemployment puts fiscal pressure on social supports like employment insurance, social assistance, re-training allowances, etc. Thus, attempts to cut spending to tame deficits may have the perverse effect of increasing existing deficits, as prolonged economic stagnation taxes both government revenues and social spending. In light of this, the IMF advises governments to consider delaying deficit-fighting measures until a more robust economic recovery is evident. Conversely, the IMF demonstrates that public investments – particularly in economies experiencing low economic growth – can significantly increase output, lower unemployment and actually bring about a reduction in the public-debt-to-GDP ratio because of the much bigger boost in output.

Debts and Deficits

Despite the demonstrated wisdom of the above approach, calls to increase spending – and deficits in the short-term – during an economic downturn face the political problem of “deficit hysteria” that is particularly acute in Saskatchewan. Due to the fiscal mismanagement of the Grant Devine-era Progressive Conservatives, the Saskatchewan public is particularly wary of accumulating debt in even the best of economic times. However, allusions to current government debt and deficits as reminiscent of the Devine years are not helpful in this regard. Despite current government debt levels, Saskatchewan’s economy is much larger than what is was in the 1980s and 1990s. While Devine-era debt reached over 40 percent as a percentage of GDP (closer to 60 percent if we include Crown debt), Saskatchewan’s current debt as a percentage of GDP is only 19.9 percent, the second lowest in the country after Alberta. Compare this to Manitoba’s 30.9 percent, British Columbia’s 26.6 percent, or Ontario’s 39.6 percent and Saskatchewan’s debt burden is relatively low, leaving the option for enhanced public spending open. As Lovely and Pinsonneault of the National Bank conclude in their analysis of Saskatchewan’s 2016 budget:

Overall then, the debt burden can be deemed low (second only to Alberta), with the interest bite very manageable, contingent liabilities fairly limited, liquidity very healthy and budget flexibility/taxing room available (should it ultimately be required).

Saskatchewan does have space to increase spending and even to increase taxes should the government deem it necessary. If the choice is between drastic public spending cuts that will only prolong the economic downturn, drive up unemployment and further exacerbate current deficits, the prudent choice would be to borrow sensibly now so as to restore the economy to a position of strength whereby deficits can be more aggressively and productively attacked in the future.

The Morality of Austerity

In addition to the economic argument against austerity, there is also a moral one that governments must consider. In essence, austerity arguments often boil down to a moral argument, as austerity is framed as the necessary “penance” for profligate spending during boom times. But austerity assumes that everyone shares in the pain of cuts equally. This is simply not true. Given that austerity measures primarily target public spending for programs and services, the effect will be to punish those that rely on these programs and services far more than those who do not. Mark Blyth – Professor of International Political Economy at Brown University – notes that the “effects of austerity are felt differentially across the income distribution.” If you “reside in the middle or the bottom half of the income and wealth distribution, you rely on government services, both indirect (tax breaks and subsidies) and direct (transfers, public transport, public education, health care). Those further up the income distribution who have private alternatives (and more deductions) are obviously less reliant on such services. If state spending is cut, the effects of doing so are, quite simply, unfairly and unsustainably distributed. Moreover, it seems particularly cruel to put the burden of cuts on those at the bottom of the income distribution who were least likely to have shared in the province’s prosperity during the boom period, and may have even been negatively impacted by the rising costs of living associated with the boom years.

Taxes and Revenues

The sad truth is that the government relied far too much on inflated resource prices as a major source of revenue during the boom period. Indeed, these extra revenues were effectively used to subsidize tax cuts that with the end of the commodity boom now appear unsustainable. The prudent course would have been to maintain or raise tax and royalty rates during the boom period to create a sizeable resource revenue or heritage fund that could have been drawn upon once commodity prices inevitably returned to earth. Such a fund would have allowed the government to maintain relatively stable spending levels even as their tax revenues fall during an economic downturn. Unfortunately, the government did not follow this course, and the current deficit position is the result. The decline of revenues now has the government contemplating certain tax increases and/or elimination of exemptions. As the government considers new sources of revenues, we would ask the government to once again contemplate the moral argument of austerity – ensuring that those least able to absorb tax increases are not asked to bear the burden of the government’s decisions.

In general, raising taxes during an economic downturn is not good policy, since what is needed most during an economic slump is for spending to increase from both the public and private sectors. But if tax revenues must be raised to fill deepening budgetary holes, then the sensible way to proceed is to focus these increases on wealthier households. Their ability to absorb such increases is obviously the strongest, which means that unlike other households, they are not likely to cut back significantly on spending in response to tax hikes. There is also an equity issue here. Over the past decade, the wealthiest households in Saskatchewan have received a disproportionate share of income growth in comparison to the bottom half of Saskatchewan families, with the boom years being particularly kind to the wealthiest in our province. As these households prospered the most under the tax regime of the current government, it seems appropriate that they should shoulder a portion of the burden during the economic downturn. For instance, in response to the recession, at least eleven U.S. states implemented a temporary surtax (between 1 to 5 percent) on high-income earners as a means to restore government revenue, while other states like New York and California introduced new high-income tax brackets and limited the amount of deductions that taxpayers could make. Saskatchewan might consider a similar temporary surtax on very high-income earners in the province as a more equitable means to raise revenue than a general sales tax increase which would disproportionately harm low-income earners who spend a larger share of their income on consumption.

Business Taxes

Perhaps the biggest beneficiary of tax changes during the boom period has been Saskatchewan’s small business. Under the current government, the small business tax rate on the first $500,000 of eligible business income has been reduced from 4.5 percent to 2 percent, making Saskatchewan’s small business tax the second lowest in the country after Manitoba. These cuts are in-line with the rest of the country that have seen provincial small business income tax reduced on average by three-fifths over the past decade. Given the size of these reductions, from an equity perspective it seems reasonable to consider raising the small business tax rate – at least temporarily. Restoring a half or even a full percentage point to the small business tax rate would still leave us competitive Alberta’s 3 percent or British Columbia’s 2.5 percent rate while generating much-needed revenue. A similar argument could be made for increasing the corporate income tax rate, which has been reduced from 17 percent to 12 percent over the past decade – part of the general trend of shifting the tax burden away from business and onto individuals. Saskatchewan’s rate is virtually identical to our neighbours with Alberta at 12 percent, Manitoba at 12 percent and B.C. at 11.5 percent. Restoring the rate to 13 percent – at least temporarily – would not significantly impact Saskatchewan’s competitiveness, particularly given that taxes – in all their forms – represent only between 3% to 11% of location-specific business costs. Instituting the above rate changes for high-income earners and business would be a much more equitable response to the economic downturn than public spending cuts and consumption tax increases.

Conclusion

As a late-comer to economic turbulence, Saskatchewan at least has the advantage of being able to assess the efficacy of policy responses by those who have gone before us. The opinion of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the U.S. Treasury is that austerity measures during an economic downturn leads to contraction – not expansion. Unfortunately, the government appears set on choosing the austerity path despite a wealth of evidence from around the world that demonstrates the futility of austerity during an economic downturn. Not only do austerity measures fail to restore growth, prolong economic stagnation, increase unemployment and exacerbate deficits, but they ask the most vulnerable in our province to foot the bill for the rest of us. Politicians who advocate austerity regularly counsel that we “all need to tighten our belts.” As Mark Blyth observes, that’s all well and good if we are “all wearing the same size pants,” but we don’t. Austerity asks those with the least space left on their belts to tighten the most. The Saskatchewan government is in its current fiscal position because it made certain choices during the economic boom that have now come back to haunt us. We have outlined certain policy choices the government could make during this time of economic downturn that ensure the most vulnerable among us don’t continue to pay the most for choices that benefitted them the least. We hope the government will seriously consider the available evidence on austerity and recognize that the path it has set upon – while perhaps politically the easiest – is certainly not the wisest.