Lise, a mother with two kids who works at a college, and her brother Dan, a lawyer, compare how the 2017 provincial budget has affected them in the last year.

Lise, a mother with two kids who works at a college, and her brother Dan, a lawyer, compare how the 2017 provincial budget has affected them in the last year.

On April 10, the Saskatchewan government tabled its 2018-19 budget. Here are 10 things to know:

In Sum. This budget, while relatively status quo, is mostly bad news for low-income households in the province. And this comes one year after a budget that announced significant cuts to social programs.

The author wishes to thank Daniel Béland, Simon Enoch, Dionne Miazdyck-Shield and one anonymous reviewer for invaluable assistance with this blog post. Any errors lie with the author.

Nick Falvo is Director of Research and Data at the Calgary Homeless Foundation. You can follow him on Twitter at @nicholas_falvo.

For those that feared that the Saskatchewan government would continue the punishing austerity they laid out in 2017, this year’s budget came as a mild relief. While the 2018 budget doesn’t restore the cuts made last year, the government appears to have opted for holding the line – offering no major tax increases while avoiding the litany of program cuts that outraged the public in the previous budget.

One of the first rules of politics is to define yourself before your opponent does it for you. This budget was the first act of newly-minted Premier Scott Moe’s government that was guaranteed to receive public attention, and for a Premier who has yet to define himself or his government, replicating what was widely seen as a mean-spirited and unfair 2017 budget would have been to court political disaster. That a politician as adept as former Premier Brad Wall could not sell austerity to the public last year left little chance that a relative unknown like Scott Moe could. Certainly, this budget was a defining moment for Moe and his government, and they appeared unwilling to wear the public opprobrium that would have inevitably resulted from a continued slash and burn approach to the budget.

That being said, while the 2018 budget is more measured in that it doesn’t replicate a 2017 budget that saw cuts and tax increases land disproportionately on the shoulders of the poor while simultaneously lavishing multiple tax breaks on corporations, it certainly doesn’t do the more vulnerable in our province any favours. The province is suspending the Saskatchewan Rental Housing Supplement (SRHS), which will force the poorest in the province to devote even more of their meagre earnings towards rent. This continues the government’s myopic focus on wrenching cost-savings from programs explicitly designed to support the poorest in the province. While the government did increase education spending by $30 million, it restores little more than half of the $54 million that was cut last year. School boards will be forced to find even more “efficiencies” in the classroom, even as student enrolment expands. As we have seen in the past, these “efficiencies” seem to fall disproportionately on special needs supports and programs.

If there is a small sliver of a silver-lining in this budget, perhaps it’s the government’s growing recognition that austerity during a downturn is bad economic policy. It’s better to allow positive economic growth fight your deficits than deep cuts that can jeopardize positive economic growth, a point the CCPA Saskatchewan Office has been at pains to make over the past few years. After two years of negative economic growth, the economic assumptions in the 2018 budget are betting that a return to positive economic growth will do much of the heavy lifting of fighting the deficit. While this is welcome, it further throws into question the wisdom of the 2017 budget cuts and the government’s embrace of austerity, all evidence to the contrary.

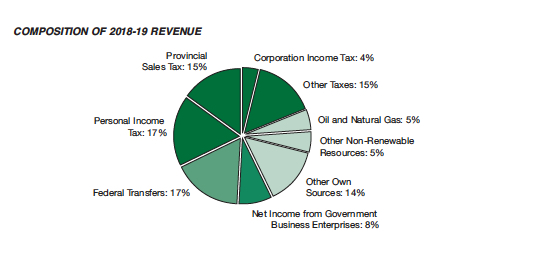

Also welcome is the government’s recognition that its planned corporate and personal income tax cut reductions were ill-advised and unsustainable. But even with these walk-backs, the paucity of the government’s current corporate income tax rate is reflected in the composition of revenues for the 2018 budget. As University of Saskatchewan Political Studies professor Charles Smith points out, the government received twice as much revenue from Crown Corporations ($1.1 billion) than all other corporations in Saskatchewan combined ($621 million). We would do well to remember this discrepancy, should the government float the desirability of further Crown privatizations in the future.

Simon Enoch is the Director of the Saskatchewan Office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

John Clarke speaks on Saskatchewan’s austerity budget and how to fight back.

As an organizer with the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP), John Clarke has been involved in poor people’s movements for over 25 years. He first became active in anti-poverty struggles in 1983, when he helped form the Union of Unemployed Workers in London, Ontario. In 1989, he was among the organizers of a province-wide March Against Poverty that helped force the Liberal government of the day to increase social assistance rates. Since 1990, John has been a Toronto-based organizer with OCAP, which has played a leading role in mobilizing against policies of economic violence. OCAP has close links with the Irish Housing Network, and John recently traveled to the UK to observe and learn from anti-austerity movements there.

In December, SaskForward began an online public consultation process that asked people across the province to answer the question, “What ‘transformational change’ would you introduce to make Saskatchewan a happier, healthier, and more prosperous place for all?”

After receiving over one hundred submissions from individuals and organizations and hosting a policy summit and discussion with over 120 participants, SaskForward releases Saskatchewan Speaks: Policy Recommendations for Transformational Change. This report puts forward a series of policy recommendations based on the ideas and suggestions Saskatchewan people shared with us.

Three key messages emerged from the ideas shared with us during the consultation process. The first is that public spending that addresses the root causes of social problems needs to be viewed as an investment that will save us money in the long run. While cuts to social spending may improve balance sheets in the short-term, they will create long-lasting health and social impacts that outweigh any initial cost-saving. Indeed, there was widespread consensus that social program cuts – even in spite of the current deficit – were ill-advised and counter-productive to the overall health of the province.

The second message that emerged from the submissions was that respondents want to see much more emphasis on new revenue streams and sources. Saskatchewan’s revenues as a share of GDP have declined from 22.4 percent in 2007 to 17 percent in 2015. Respondents were unified in their call for the government to consider new revenue sources, with a strong preference for increased progressivity in the provincial income tax system.

Lastly, there was a real appetite for a grand vision for the province, particularly in regards to energy and the environment. Many respondents believe that Saskatchewan – with its ample renewable resources and provincial crown corporations – is uniquely situated to take advantage of the nascent green energy economy given the appropriate direction and investment by the provincial government.

Despite the province’s current economic woes, there was a tremendous optimism in the ability of the province to become a more just and sustainable place in the future. We want to thank the people of Saskatchewan for sharing their visions for the province with SaskForward. We certainly hope the government and the rest of the Saskatchewan public will seriously consider the thoughtful and inspiring ideas we have collected in this report.

Download the full report: SaskForward – Sask Speaks (03-15-17)-4

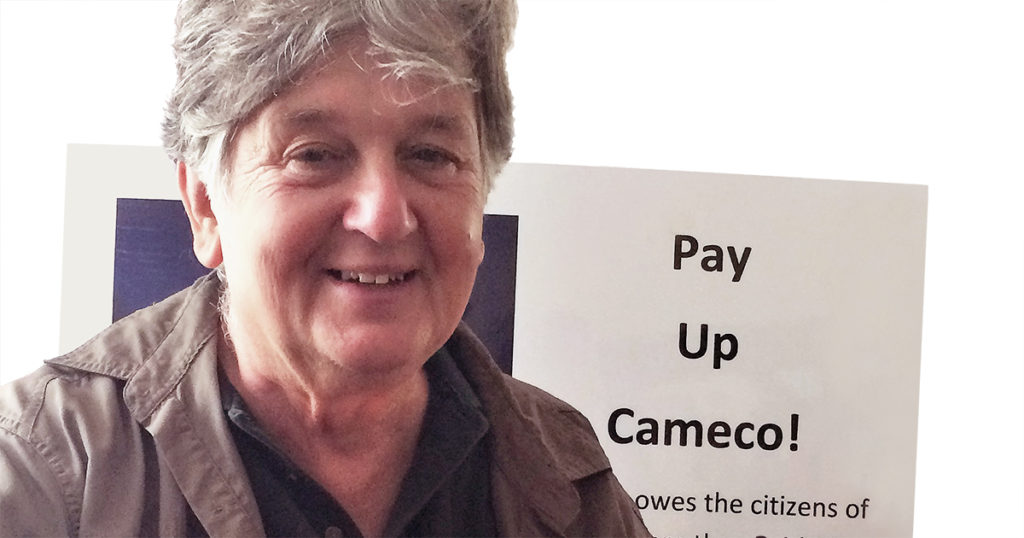

Make Cameco Pay Up

Saskatchewan citizens are conducting an ongoing campaign to have Cameco – one of the largest uranium companies in the world – pay the $2.2 billion bill that it has accumulated in unpaid taxes.

Cameco has dodged every attempt to have them pay the people of Canada and Saskatchewan what they have stolen. In a story on April 25th, 2016, The National Observer asked if Cameco has “engineer[ed] the largest tax dodge in Canadian History.”

Through donations to hospitals, sponsorship of charitable causes, and bringing in performers like Sarah McLachlin, Cameco has perfected its “Cameco Cares” image of social responsibility. The flip side is much darker. Despite enormous profits over many years – with the help of a tax avoidance scheme, Cameco has caused disruption in the lives of many communities of northern Saskatchewan. Last year the Rabbit Lake mine was closed down, resulting in the loss of 500 jobs. More recently, another 120 jobs have been lost in Cameco operations at the Cigar Lake, McArthur River, and Key Lake mines. Half of people working for Cameco in the North are First Nations or Metis.

Cameco argues they are not making enough money.

The Moteley Fool, a financial advisory web page, describes how Cameco works its finances: “During a six-year period ending in 2012 Cameco’s Canadian operations racked up a cumulative $1.3 billion in losses. Meanwhile, over the same period, the company’s Swiss subsidiary recorded $4.3 billion in profits.” What exactly is going on?

It all dates back to 1999. Cameco set up a subsidiary in Luxembourg, eventually moving it to a low-tax jurisdiction in Switzerland. It then entered into a 17-year contract with that subsidiary, one that would see Cameco’s Canadian operations sell its uranium to its Swiss subsidiary. The price per pound would be fixed for the entire time and “reflected market conditions,” as put by CFO Grant Isaac in 2013.

As the Motley Fool explains, “When the uranium price was severely depressed in 1999, the company’s executives thought this price would rise. They were absolutely right. As a result, Cameco’s Canadian operations began selling uranium for below-market value, resulting in losses. Meanwhile, the Swiss subsidiary was able to buy at below-market prices, ensuring big profits. These big profits faced minimal taxes.”

Cameco is before a CRA court right now to ascertain their guilt in this method of tax avoidance. CRA started looking at Cameco in 2006 – taking ten years and many delays to get to this point. A petition campaign supported by Canadians for Tax Fairness, Sum of Us, and Saskatchewan Citizens for Tax Fairness received over 36,000 signatures. It called on the Federal and Provincial governments to have Cameco pay up.

Cameco’s tentacles go wide and deep in controlling any sort of opposition in Saskatchewan. During a recent Cameco lockout of workers a short video was done on the line interviewing Cameco workers. For one day it circulated on the internet and contained a comment about health and safety conditions in the mines. A worker asked that it be taken down out of deep concern about Cameco’s reaction.

Even though Saskatchewan is in the midst of an economic crisis Premier Wall refuses to pursue the monies owed by Cameco to the Province of Saskatchewan. An estimated 800 million or more could come back if Cameco paid what they owe. That would certainly take the pressure off all the cutbacks and other destructions happening to Saskatchewan’s social and other infrastructures, and particularly communities in northern Saskatchewan. When one sees the closure of the Nortep program in northern Saskatchewan, the community of La Loche still waiting for crisis support services and people who can find housing to live in their community, the freeze and cut backs on 64,000 government workers, the ending of the affordable housing program, cutbacks on healthy baby/healthy mother programs etc – one sees the trail of destruction of Cameco not paying up the millions upon millions they owe to the Saskatchewan people.

The Premier of Saskatchewan has lauded Cameco as the driver of development in the northern Saskatchewan. In 2013 he described Cameco as the best program for First Nations and Metis people. But, seeing Cameco leading them through a boom and bust economy, communities in northern Saskatchewan are asking for much more.

In response to the most recent Cameco cutbacks, Bucky Belanger, NDP MLA in northern Saskatchewan, underscored “the need to expand tourism, forestry, oil and gas development and other industries in the north”.

The problem with areas of “development” such as oil, gas, and forestry is that they still are a part of a boom and bust economy and extract resources from a community without giving much back.

In the late 1900’s there were some real efforts to bring communities of the North together to look at how they would build their own Indigenous economy that would support jobs and resource wealth staying in the north. There is a real need to revive and build on those discussions. A northern economic and social plan done by and with communities of the North would go a long way in reducing the dependency on multi-national corporations that extract but do not give back.

The Cameco situation raises important concerns and questions for Saskatchewan citizens about tax evasion, and Cameco’s sales of uranium internationally also raise serous moral questions that Saskatchewan citizens need to address. The uranium sale a year ago to India – and lauded by Premier Wall- was to a country that has refused to sign the nuclear non proliferation treaty.

Cameco should be answerable and accountable on many fronts including tax dodging, the instability of communities that rely on Cameco as a single source of employment, the health and safety of uranium miners and their communities, the impact on the environment of uranium extraction, and the potential dangers of selling uranium on international markets.

Peter Gilmer of the Regina Anti-Poverty Ministry identifies how the Government of Saskatchewan’s cut-backs are impacting the province’s most vulnerable residents.

Re-thinking Deficits and Austerity

I want to discuss the elephant in the room that haunts any of the subsequent policy discussions we will have the rest of the day and that is obviously the current economic health of the province and the government’s financial situation. How we view the current economic situation will determine whether we believe we have choices going forward or whether we have to accept the government’s narrative of deep and immediate cuts as inevitable. So I’d like to use my time this morning to challenge some of the economic assumptions that limit the horizon of what is possible – even in the current economic situation.

I certainly think we can see some of these economic assumptions at work when we look at the scope of the transformational change undertaken by the government so far.

It’s pretty clear that the Saskatchewan government’s “transformational change” agenda is really a clever euphemism for austerity. Everything that the government has done under the banner of transformational change has been to cut, down-size, roll-back or eliminate. More often than not, these cuts have been directly at the expense of the province’s most vulnerable – such as the cuts to Seniors and Children’s Drug Plans, reduced funding for the Alternative Measures sentencing program and Aboriginal Courtworker Program, and claw-backs to some social assistance programs. Most recently the government has eliminated the 251 custodial jobs – the lowest paid of most government employees and is threatening to eliminate more.

So the government has been entirely focused on the cost-side of the ledger to the neglect of any revenue-generating ideas. Although I suspect we will see some tax increases – most likely a regressive sales tax increase – by the next budget. The government appears to view transformational change as an exercise in cost-cutting, to the detriment of any alternatives.

Now obviously the justification for these cuts is the size of the provincial deficit and the government’s insistence that we have to return to balance as quickly as possible (Surplus by 2018 if we are to believe the Finance Minister).

But If we believe that these are the wrong choices to make, and that there are alternatives that do not disproportionately burden those most vulnerable in our province, then we need to stop buying into the deficit hysteria that allows the government to justify cuts as the only means forward.

Every time we decry the size of the deficit or liken it to the Devine-era, we are, intentionally or not, playing into the government’s frame – that it is the deficit that matters – not unemployment or preserving social programs or the environment or ensuring the most vulnerable in our province are taken care of.

That’s not to say that we can’t criticize why we are in a deficit position, particularly after nearly a decade of booming commodity prices, but if we act as if the mere existence of the deficit is akin to the sky falling, then we are just painting ourselves into a corner when it comes to possible remedies.

So I think we need to put the deficit in perspective in relation to our current debt levels so we can better see what choices are available to us. Saskatchewan’s economy is much larger than what is was in the 1980s and 1990s. So while a billion dollar deficit in 1991 was cause for grave concern, I don’t think it warrants the same alarm as it did thirty years ago. So let’s look at comparisons. While Devine-era debt reached over 40 percent as a percentage of GDP (closer to 60 percent if we include Crown debt), Saskatchewan’s current debt as a percentage of GDP is only 19.9 percent, that’s the second lowest in the country after Alberta. Compare this to Manitoba’s 30.9 percent, British Columbia’s 26.6 percent, or Ontario’s 39.6 percent and Saskatchewan’s debt burden is relatively low, leaving the option open for maintaining current spending levels and even enhancing them.

Indeed, as the National Bank concludes in their analysis of Saskatchewan’s 2016 budget:

“Overall then, the debt burden can be deemed low (second only to Alberta), with the interest bite very manageable, contingent liabilities fairly limited, liquidity very healthy and budget flexibility/taxing room available (should it ultimately be required).”

So we have room to manoeuvre, which means we don’t have to try and balance the budget immediately as the government insists. Which means we don’t have to accept massive cuts to public services and the public sector as an inevitability.

Does that mean we don’t have to deal with the deficit? Of course not, but we can choose how and when to deal with the deficit and on grounds that are more favourable.

Let me give you an example, many of you probably remember Paul Martin’s “Hell or High-water” budget in 1995. That’s when Martin as Finance Minister in the Chretien government vowed to defeat the federal deficit “come hell or high-water.”

So Martin made probably the most dramatic cuts to health and social transfers in Canada’s history in his effort to tackle the deficit. That budget is a large part of how the federal government managed to extract itself as a full partner for funding provincial health and other social programs. So these cuts still reverberate with us today.

And like Saskatchewan today, Martin conducted his cuts during a recession – and the cuts had the effect of actually contracting the Canadian economy for a short period of time. But by 1997 Ottawa was back to surplus. So this is a success story right? Well, not if you compare it to other industrialized countries that were also fighting deficits during that period. In fact 18 other countries balanced their budgets during that same period – slightly later than Canada, but balanced them nevertheless. And they did this by either maintaining or expanding spending. How did they achieve this?

Well the economic conditions changed, the world economy recovered and in a positive growth environment its a lot easier to balance budgets – more people are working, increasing tax receipts and less are relying on social supports. So governments are bringing in more revenue while spending less. That makes fighting deficits a lot easier than in a recession when tax receipts are low and you are spending more on social supports. Indeed, as Economist Jim Stanford demonstrates, had the Chretien government merely held the line on spending and merely waited for positive growth to return, the deficit could have been balanced by 1999, only two years later, and without any of the massive dislocations caused by such traumatic spending cuts. And it’s important to note that for the most part, those cuts were never restored, even during the period of year-after-year surpluses that the federal government enjoyed.

But this is what I mean by tackling the deficit on grounds that are more favourable. It is much easier and far less painful to tackle deficits when you are in a positive growth environment.

But the second important thing to keep in mind is that implementing austerity during an economic downturn can actually hinder the return to positive growth. As I mentioned, the Martin cuts actually had the effect of briefly contracting the economy. The fact that austerity measures implemented during a downturn actually contract the economy is pretty much the received wisdom now.

Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – once a champion of fiscal austerity – has been forced to admit this. Assessing 30 years of evidence, the IMF unequivocally concludes: “In economists’ jargon, fiscal consolidations [austerity] are contractionary, not expansionary. This conclusion reverses earlier suggestions in the literature that cutting the budget deficit can spur growth in the short term.”

Moreover, the IMF demonstrates that adoption of austerity measures during an economic downturn is “likely to lower incomes—hitting wage-earners more than others—and raise unemployment, particularly long-term unemployment.” Such effects will have the consequence of exacerbating deficits as falling incomes diminish government tax receipts while growing unemployment puts fiscal pressure on social supports like employment insurance, social assistance, re-training allowances, etc.

Thus, attempts to cut spending to tame deficits may have the perverse effect of increasing existing deficits, as prolonged economic stagnation taxes both government revenues and social spending. In light of this, the IMF advises governments to consider delaying deficit-fighting measures until a more robust economic recovery is evident. Conversely, the IMF demonstrates that public investments – particularly in economies experiencing low economic growth – can significantly increase output, lower unemployment and actually bring about a reduction in the public-debt-to-GDP ratio because of the much bigger boost in output. In fact, the IMF concludes that government projects financed through debt issuance have stronger expansionary effects than budget-neutral projects that are financed by raising taxes or cutting other spending.

If we want a good example of how austerity can backfire and produce the very thing you are trying to avoid, we need only take a look at the United Kingdom over the past few years. In response to the deficit racked up bailing out banks during the financial crisis the Cameron government initiated an unprecedented series of austerity measures, cutting government spending across the board by ten percent, including the elimination of 300,000 public sector jobs.

What was the result, well the British economy contracted three times and debt levels went up – not down. When the Cameron government took power debt in the U.K was about 70% of GDP, today it stands at 85%. The cuts did not work – they did the exact opposite, they contracted the economy and increased the debt burden.

I know this seems counterintuitive to many, how can cutting spending increase debt?

The problem is that many governments want us to think about government finances the same way we think about our household finances.

So if I’m in debt, as long as my income stays constant, and I cut my spending, I can pay down my debt.

The problem is that the government is not a household. Cuts in one area – say public sector jobs – increases costs in other areas – say social assistance or re-training. Indeed we have already seen this here in Saskatchewan. The government just announced that because there are more people accessing social assistance programs than expected, the government needs to spend an extra $55 million.

Moreover, if people lose jobs or see their wages rolled-back, the government’s income doesn’t stay constant as tax revenue decreases as people are less likely to spend thereby reducing the government’s take on sales taxes, and if their incomes are reduced or eliminated they are obviously not going to be paying much in the way of income taxes. Once again, the government has seen a decrease of $400 million in expected tax receipts during the downturn.

Same thing with other programs, so if you cut alternative sentencing programs, more people end up in prison. Low and behold, Saskatchewan has more people in correctional facilities than the government expected, creating the need for an extra $10.3 million.

This creates a vicious cycle where you are trying to make cuts on one side to try and outdo the increased expenses you experience on the other side.

So the government’s finances are not at all like a household. Cuts in one area can increase expenses in another, while draining revenues. We should be wary of anyone who want to simplistically equate the government’s finances with a household.

The fact is that austerity doesn’t just not work – it produces the exact opposite of what austerity is supposed to achieve. Instead of reducing deficits and restoring positive growth – it induces contraction and increases debt.

So the question must be asked, if austerity has proven to be so unsuccessful, why do governments pursue it?

As Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman observes, the “primary purpose” of austerity,“is to shrink the size of government spending – to make the state leaner … not just now, but permanently.”

And as I mentioned before with the Paul Martin austerity budget in 1995, those cuts were never fully restored. Even as the federal government posted surplus after surplus in the years following.

So I think we need to be wary about the whole exercise of austerity because its effects are not temporary, they may very well limit the size and scope of what government can accomplish in the future.

So as we talk today about possibilities for the future here in Saskatchewan, I would ask you all to consider whether pursuing austerity right now helps or hinders real transformational change.

Simon Enoch is Director of the Saskatchewan Office of the Canadian centre for Policy Alternatives. See here for more on the failure of austerity economics.

Upstream: Toward a Provincial Strategy on Obesity Prevention

We have heard that Saskatchewan has a financial deficit of about $1 billion. We know that a large proportion of our Saskatchewan budget, perhaps 40 percent, is devoted to what is called “health care” although more correctly it should be called illness care and treatment. A significant portion of that cost is what the provincial government pays for treatment of diabetes and other obesity-related illnesses. We also know that prior to 1960, diabetes of type II was relatively rare in Saskatchewan whereas now it is considered an epidemic.

What is called for here is real “transformational change,” not just continuing the current treatment approach, but an upstream approach, a prevention approach, dealing with causes, and gradually reducing treatment costs over time.

In this submission we claim that obesity is preventable, and with it, many obesity-related illnesses, such of diabetes and the complications associated with diabetes. We claim that in our society we presently have the knowledge and skill to prevent obesity but we are not putting a sufficient priority on prevention. We claim that increasing the current health promotion and disease prevention budget to 3 percent from the current 1.4 percent of total health expenditures by Saskatchewan Health would have a major impact in reducing obesity and reducing overall “health care” costs. We suggest that the following claim be pondered, at least briefly, rather than dismissed as outrageous:

“…if all residents of Saskatchewan had healthy weights (BMI = 20 to 24.9) the province would save up to $260 million a year… If all Saskatchewan residents had healthy weights and did not smoke, the province could save up to $570 million a year.” (Colman 2001: 20)

Finally we claim, if we do not increase substantially the current efforts at prevention, that obesity, diabetes and related costs shall continue to climb dramatically, with major negative impacts on all Saskatchewan residents.

________________________________

“Widespread increases in physical inactivity and caloric intake have led to a global epidemic of overweight, obesity and diabetes. The reasons for these trends are multifaceted and complex. However, major drivers include the ubiquity of high-calorie, low-cost convenience foods, increased portion sizes, and a way of life that encourages sedentary behaviour, such as sitting at computers, in front of television screens, and in cars” (Booth 2015).

For the first time, in 1997, the World Health Organization (WHO) referred to obesity as a “global epidemic.” For the first time in human history, the number of overweight people in the world now equals the number of underfed people, with 1.1 billion in each group (Colman 2001).

Obesity and diabetes have reached epidemic proportions in Canada. Obesity is a major risk factor for diabetes and many other chronic diseases, all of which place major costs on the health care system and the economy as well as the individual and family involved. For example, obese Canadians are four times more likely to have diabetes than those with healthy weights. Obesity was not a problem several decades ago. Obesity is preventable. A cost-effective strategy must take an “upstream” approach, aiming at prevention of obesity, focussing primarily on adequate physical activity and a healthy diet from an early age and secondarily on the physical environment.

Obesity is a sensitive subject. Our intent here is not to cast blame, to make overweight people feel bad about themselves, or to allow healthy weight people to feel smug. “On the contrary, it is to suggest that Saskatchewan could take the lead in turning around a highly destructive global trend, and to encourage communities, schools, policy makers, health professionals and ordinary individuals to work together to improve the health and well-being of all our citizens” (Colman 2001). Pursuing healthy weights should not be viewed as simply a purely individual responsibility but a challenge calling for a “whole-of-society” approach (Obesity in Canada, Canada Senate Report, 2016:18).

Extent of Obesity and Diabetes

The extent of obesity in Canada is “high and rising:” even more alarming is the recent increase among children and youth. Two-thirds of Canadian adults are overweight (BMI= 25.0 to 29.9) or obese (BMI=>30.0), (where BMI or Body Mass Index = weight in kg/height in cm squared). This has increased dramatically over the past 25 years, roughly doubling in adults. One quarter of Canadian adults and 8.6 percent of children and youth aged 6-17 are obese according to measured height and weight data from 2007-2009 (Obesity in Canada, p. 4). Another source states that in the period 1985 to 2011 obesity tripled from 6 percent to 18 percent of the Canadian population.

Other sources show similar findings: obese Canadians are 20.2 % of the population; overweight and obese men are 62 % and women 46 %. Another source shows that among non-aboriginals, age 18 and over, 2009-2010 data, the percentage who are overweight or obese is 51.9%; among First Nations on-reserve it is 74.4%; among First Nations off-reserve it is 62.5%, 2008-2010 data (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2011).

In Saskatchewan, nearly two-thirds of residents have an unhealthy weight, second only to New Brunswick (Colman 2001). In Saskatchewan, approximately 57 percent of adults and 20 percent of youth are either overweight or obese. Regarding diabetes, it is estimated that the number of people living with diabetes in Saskatchewan will grow to 100,000 in 2017, up from 97,000 in 2016, and will increase by 35 percent in the next decade. In addition, a further 176,000 are expected to be living with pre-diabetes and another 43,000 living with undiagnosed diabetes (Canadian Diabetes Association, 2017??). Not only is the number of people with diabetes growing, but so are the serious complications they experience such as heart attack, stroke, kidney failure, blindness and limb amputation, all of which incur serious costs on the individuals, families and the province.

Impacts

Obesity is a risk factor in many chronic diseases. Obesity significantly increases the risk of Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension (high blood pressure), high cholesterol, osteoarthritis and certain types of cancer. In turn, diabetes leads to serious complications as listed above. Estimates of the cost of obesity in Canada range from $4.6 billion to $7.1 billion annually (2006). For diabetes alone the cost in 2000 was $2.5 billion a year (Diabetes in Canada, p. 47).

In Saskatchewan obesity is the second-leading preventable cause of death after cigarette smoking. It is estimated that more than 960 Saskatchewan residents die prematurely each year due to obesity-related illness, compared to 1,200 deaths due to tobacco and about 100 road accident deaths.

Obesity-related illnesses cost the Saskatchewan health care system an estimated $120 million dollars annually, or 7.3% of total direct health care costs. When productivity losses due to obesity, including premature death, absenteeism and disability are added, the total cost of obesity to the Saskatchewan economy was estimated at between $230 million and $260 million a year, equal to 1% of the province’s Gross Domestic Product. If present trends continue, these costs could surpass the direct and indirect costs of tobacco smoking, currently about $311 million a year (Colman 2001).

A recent study indicates that diabetes alone costs Saskatchewan’s health care system $99.8 million a year in direct costs including hospitalization, doctor visits, dialysis and inpatient medications.

Although obesity represents a burden for some, it is a boon to economic growth and the GDP. The obesity epidemic is a boon for the pharmaceutical industry. New factories need to be built to produce more insulin and other anti-diabetic drugs to meet the skyrocketing demand from those with diabetes, as global incidence of diabetes is expected to double to 300 million people by the year 2015. Like war, crime and pollution, illness can make the economy grow more rapidly than peace, health and a clean environment. In the USA, liposuction is the leading form of cosmetic surgery; diet and weight loss industries contribute $33 billion to the U.S. economy annually (Colman 2001: 23).

Causes

Obesity involves a wide and interactive range of behavioural, biological/genetic, and societal factors. Health behaviours or lifestyle factors, primarily eating healthy food and having adequate physical activity, are themselves influenced by deeper societal factors like stress and work patterns.

Poor eating habits (including low consumption of fruits and vegetables and high consumption of refined carbohydrates and sweetened beverages (Bray 2003), particularly high-sugar, high-salt, fast food, show a strong association with the prevalence of obesity. Eating habits, healthy and unhealthy, are learned at an early age, like developing a taste for vegetables or for foods with sugar and salt: much food marketed as baby food has considerable levels of salt and sugar. Access to healthy food also is important: low income and distance from a food store may lead to more use of closer convenience stores with poorer food choices. For those with higher incomes, sedentary lifestyles, longer work hours, rising stress levels, may all contribute to increasing unhealthy weights. In Saskatchewan residents eat out more often than they used to and one quarter experience high levels of chronic stress (Colman 2001).

The food industry contributes $30 billion in advertising to the U.S. GDP (Gross Domestic Product), more than any other industry does, and much of it promotes the very foods that cause obesity: much of it targets children and youth. In Canada, current support for education or information programs aimed at nutritional illiteracy is infinitesimal in comparison: it appears that we are simply leaving this topic to the food industry.

Physical inactivity also has a strong association with obesity for both men and women. In the USA, which does not have universal Medicare, some HMOs (Health Management Organizations), finding that people who are more active use fewer medications, encourage their clients to participate in physical activity by subsidizing gym fees,

Less than half of Saskatchewan residents exercise regularly (three or more times a week), the second lowest rate of activity in Canada, and a quarter either never exercise or exercise less than once a week. Saskatchewan residents watch an average of 3.25 hours of television each day (Colman 2001). Television watching often begins at an early age, followed by video games and smart phones.

Although lifestyle is the major risk factor for obesity, societal factors such as family history, ethnic background and socioeconomic status, as well as the physical environment also play a significant part. Obesity is correlated with low educational level, poverty and rural residence; obesity also is generally higher in Aboriginal (37.8%) than non-Aboriginal people. Climbing obesity rates are less the fault of individuals and more a consequence of changes in the food environment (e.g. a huge increase in fast food outlets) and a decrease in physical activity demands in daily living, resulting in an “obesogenic environment” making it too easy to eat poorly and remain sedentary (Obesity in Canada, Senate Report, 2016:8)

A more recent consideration regarding obesity that is gaining momentum among public health officials, at least in urban areas, is the potential to design or redesign the built environment in which we live—including buildings, parks, transportation systems and overall communities—to promote active, healthy living. Numerous studies have suggested a link between neighbourhood characteristics – including urban design, the presence of recreational spaces and “foodscapes” –and the physical activity and dietary patterns of local residents. Thus there is growing evidence from large, observational studies that neighbourhoods that provide more opportunities for walking and cycling have lower rates of obesity and diabetes. Collectively, this evidence suggests that population interventions targeting the built environment may have long-term health benefits (Booth 2015).

Saskatchewan Ministry of Health

Saskatchewan Ministry of Education: Children and Youth

Other Public Policy

General

Questions

References

Beveridge, Angelina. Resolution by Saskatchewan Registered Nurses Association (SRNA) at Annual General Meeting 2008

Beveridge, Angelina. Resolution by Saskatchewan Registered Nurses Association (SRNA) at Annual General Meeting 2008

Beveridge, Angelina. Toward a Provincial Strategy on Obesity Prevention and Management, SRNA Newsletter, August 2013

Booth, Gillian. Lifestyle, the built urban environment and social engineering. International Diabetes Federation Conference, Vancouver 2015.

Bray, GA. Low CHO diets and realities of weight loss, JAMA 2003, 289. pp.1853-1855.

Canadian Diabetes Association. The Cost of Diabetes in Saskatchewan: the Saskatchewan Diabetes Cost Model. (from CDA, An Economic Tsunami: the Cost of Diabetes in Canada, 2009)

Canadian Diabetes Association/Diabetes Educator Section, Saskatchewan Newsletter, Update for members, Winter 2017, “New 2017 – Saskatchewan Diabetes Rates Rising, Report indicates urgent changes needed”

Colman, R. Cost of Obesity in Saskatchewan. Glen Haven, NS: GPI Atlantic, Jan. 2001. Retrieved 2013/08/12, http://www.gpiatlantic.org/pdf/health/obesity/sask-obesity.pdf

Obesity in Canada: A Joint Report from the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2011. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/hp-ps/hl-mvs/oic-oac/assets/pdf/oic-oac-eng.pdf

Obesity in Canada: A Whole-of-Society Approach for a Healthier Canada. Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology, 2016. Retrieved 2017/01/30, https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/421/SOCI/Reports/2016-02-25_Revised_report_

Diabetes in Canada 2011: Facts and figures from a public health perspective. Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, 2011. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cd-mc/publications/diabetes-diabete/facts-figures-faits-chiffres-2011

Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, Inspiring Movement: Towards Comprehensive School

Community Health: Guidelines for Physical Activity in Saskatchewan Schools. Feb. 2010. http://www.education.gov.sk.ca/inspiring-movement

Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, Nourishing Minds: Towards Comprehensive School Community Health: Nutrition Policy Development in Saskatchewan Schools. Oct. 2009. http://www.education.gov.sk.ca/nourishing-minds

Angelina Beveridge is a retired diabetes nurse educator with the Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region. Daniel Beveridge is a retired University of Regina professor.

Contact:

Daniel M. Beveridge danmbeveridge@gmail.com

Angelina Beveridge Angelina.Beveridge@gmail.com

Introduction

The “transformational change” promised by the Saskatchewan government in early 2016 has not materialized. Instead, Saskatchewan has primarily witnessed a series of knee-jerk service cuts and austerity measures, driven by desperation to reduce costs by any means possible in the face of a massive budgetary deficit.

An important first step in achieving true transformational change is to recognize that the provincial government’s adversarial attitude towards its public services and public workers, and its increasingly privatized approach to public service delivery, are not benefitting Saskatchewan people. A change in attitude and approach is needed. The Saskatchewan government needs to dispense with the myth that the private sector is inherently more efficient and cost-effective; it needs to recognize that reactionary short-term budget cutbacks do more harm than good; and it needs to emphasize the economic well-being of the province as a whole over the gains of a few businesses.

To that end, following are recommendations for three policy decisions that the Saskatchewan government can make in the immediate term, in order to mitigate the dire economic circumstances facing Saskatchewan and begin reshaping its approach to public service delivery. Each of the points below could be elaborated on considerably (a discussion of the quality of privatized public services, or of the human impacts of layoffs and service cuts, could easily triple the size of this brief), but for the sake of brevity these points are limited to economic considerations.

1.) Keep needed workers on the government payroll, instead of depending on expensive consulting firms.

Over the past several years, the amount spent on consultants’ fees by the government of Saskatchewan has grown at a tremendous and unreasonable rate. From $31 million in 2008, spending on consultants by all government ministries reached $117 million in 2014 – a 276% increase.[1]

That rate of increase has far outstripped the growth of provincial expenditures as a whole. From 2008 to 2014, total government spending rose from $8.04 billion to $12.01 billion, a 49% increase – meaning that consultant spending grew 5.6 times faster than the budget overall.

The great majority of this spending – $101 million of the government-wide $117 million total – was spent by three ministries: Health, Central Services, and Highways and Infrastructure. Spending on consultants soared in these ministries between 2008 and 2014, rising 582% in Health and an astounding 780% in Highways. (Central Services increased its spending by “only” 69%, but as it was by far the biggest user of consultants at the outset, this still accounted for an increase of over $10 million.)

The hiring of consultants by government ministries is not, in and of itself, a problem. Consultants can and do serve a useful purpose. They provide temporary access to individuals with specialized knowledge and skills, in cases where it would be uneconomical to keep those individuals on government’s payroll.

The use of consultants on the scale practiced by the Saskatchewan government in recent years, however, is very problematic. Consultants come at a premium price compared to in-house government staff, so using them instead of hiring government workers is not cost-effective. In two of the most consultant-heavy ministries, however, replacing internal staff with consultants is exactly what happened.

In the Ministry of Highways, consulting costs are primarily directed towards private engineering firms, while the Ministry of Central Services makes extremely heavy use of information technology consultants. These are not occupations where demand is limited or unpredictable – even with the end of Saskatchewan’s nearly decade-long boom, there is no shortage of highway construction and repair projects in need of engineers, or of government computer systems to be maintained and upgraded.

Despite this, a deliberate choice was made to replace existing government engineers and IT professionals with private consultants, according to policies adopted and announced by the government. [2]

This was a costly move for the province. Highway engineering firms, for instance, typically charge between 1.9 and 4.3 times as much as it would cost to have an in- scope ministry employee do the same work, and all indications are that this cost imbalance exists for out-of-scope engineering staff as well. [3] IT consultants are similarly expensive: in a review of contracts that SGEU obtained via a freedom of information request, two major consulting firms billed the province between $100 and $310 per hour per employee.

Unlike in Highways and Central Services, it’s not clear in the Ministry of Health that consultants are taking work directly from in-house staff. It’s not readily apparent what Health receives in exchange for its hefty annual expenditure on consultants (which was nearly $20 million in both 2013 and 2014) – though its four-year, $33 million Lean contract with U.S.-based consultants likely accounts for much of it.

The Lean project raises the prospect that Saskatchewan’s runaway consulting budget isn’t just used to overpay for needed services – it may also be paying for work that Saskatchewan could simply do without. According to a study by the University of Saskatchewan’s School of Public Health, Saskatchewan spent $1,511 for every dollar saved through Lean.[4] The $33 million spent on the Lean consulting contract could clearly have returned better results for Saskatchewan people if it had been used to hire more frontline health workers.

For a government desperate to reduce a billion dollar deficit, cutting back on consultant use is an ideal move. Focusing government expenditure on in-house employees will save money, help avoid expensive mistakes such as Lean, and ensure that public spending ends up in the hands of local workers who will spend it locally – instead of going to the owners and shareholders of consulting firms.

The provincial government has already acknowledged the value in cutting back on consultants. In the provincial government’s 2016-17 mid-year financial update, the Ministry of Highways announced that it would save $700,000 through the “reduced use of consultants” – and notably, the Ministry included this reduction in a list of “initiatives with minimal impact.”

This is an excellent first step – but government can take it much further.

2.) Direct public expenditures towards Saskatchewan workers, not out-of- province corporations

The current Saskatchewan government has worked steadily to redistribute public spending away from local workers, and towards the profits of businesses that are often based outside Saskatchewan and even Canada. This has been accomplished by the contracting out of public services, and in at least one notable case, the partial shutdown of a highly profitable government business operation.

When publicly-run businesses and services are transferred to private-sector control, the first casualty is almost always compensation rates for workers. Especially in jobs requiring lower levels of education and expertise, government employment tends to offer wages and benefits significantly higher than private employers are willing to offer. Accordingly, the first step in the privatization of a government service or agency is usually the dismissal of the existing government workforce, to be replaced by a complement of private employees earning significantly lower wages and receiving greatly reduced benefits.

While the Saskatchewan government has always framed this change exclusively as a savings for the province, it is better understood as a three-party transfer of wealth: money that formerly flowed to workers instead accrues partly to government – in the form of reduced payroll costs – and partly to the new private operator of the service or business, in the form of fees it collects to deliver the service or profits it generates by running the business. The result is that, while government budgets may show some benefit, the province as a whole is left poorer as workers see their spending power drop.

Small-scale examples of this sort of wealth transfer have routinely occurred in Saskatchewan for at least the past decade. Over the past four years, however, the scale of privatization and contracting out – in terms of the dollar value involved and the number of employees affected – has increased greatly. This is evidenced by three major instances of contracting-out, and one major privatization, which have occurred since late 2013.

In December 2013, the provincial government announced that it was closing Saskatchewan’s five publicly-owned hospital laundry facilities, and contracting with Alberta-based K-Bro Linen Services to process the linens at a new private laundry facility in Regina. Shortly before receiving the contract, K-Bro approached a Saskatchewan union to offer a 10-year contract for local workers that would pay between $10.75 and $13.50, compared to the hourly rates of between $15.61and $19.99 then earned by public laundry workers.[5]

When the K-Bro deal was studied by University of Winnipeg economists, they concluded the privatization would result in “a redistribution of income from workers and other residents of the province in favour of a private corporation whose shareholders reside outside of the province,” and that the decision would “decrease income of the residents of Saskatchewan between $14 and $42 million over the next 10 years when compared to public options.”[6]

The privatization of laundry services was followed, in August 2015, by the announcement that a contract to provide food services in correctional facilities had been awarded to the U.K.-owned multinational corporation Compass Group. 62 correctional cooks were laid off, and replaced by a newly-hired group of Compass workers. While government-employed corrections cooks generally earned wages in the $20-$30 range dependent on experience, Compass posted ads for replacement jobs with wages starting at $13.03 or $14.25.

The Saskatchewan government’s next major privatization initiative was to shut down a large segment of the Crown corporation responsible for retail liquor sales, while inviting select private businesses to take the place of publicly-owned liquor stores (as well as allowing them to open 11 new greenfield private stores.) 39 public liquor stores are now slated to be shut down as soon as private replacements are up and running, a move that will cost 116 full-time equivalent jobs as store and head office staff are laid off.[7]

By far the largest beneficiary of liquor privatization has been Nova Scotia-based Sobeys Inc., which was given licences to open nine stores in Saskatchewan’s most profitable locations. Alberta-based Liquor Stores NA and B.C.-based Metro Liquor were also awarded highly-profitable locations in Regina and Saskatoon. While Sobeys, Metro, and Liquor Stores NA do not advertise their pay rates, it is a safe assumption to conclude that their Saskatchewan retail employees will earn far below the $18.99 per hour offered at the bottom of the public liquor retailer’s pay scale.

Less than two months after handing out the licenses for new private liquor stores, the Saskatchewan government announced a contracting-out plan that would cost even more public jobs. On January 12, the province posted a tender to provide janitorial services in 98 government buildings, a move that would put 251 government-employed cleaners out of work. While almost all of those workers occupy the lowest position on the public service pay scale, there is still plenty of room for their wages to fall in an industry that frequently pays minimum wage or just above.[8] Such a cut to pay for cleaning staff would, of course, be necessary in order to allow a private firm to turn a profit off of its contract with government.

There is a clear pattern in the examples above. When government decides to privatize or contract out, the immediate effect is always a sharp drop in the earnings of the workers providing the service, with a significant portion of the former wage costs absorbed as profits by the business now in control. What makes this especially regrettable is that, as shown in the examples above, often these profits do not even accrue to Saskatchewan companies. Money that formerly went to local workers instead leaves the province entirely – it flows to K-Bro and Liquor Stores NA in Alberta, to Metro Liquor in BC, to Sobeys in Nova Scotia, and to the Compass Group head offices in the U.K.

Throwing public employees out of decent-paying jobs, and replacing them with private- sector workers earning the lowest wages possible while businesses pocket the difference is not a sound plan for economic recovery. Local workers spend money locally; the decent wages paid by Saskatchewan’s public sector go towards supporting local business, and are partially returned to government through income and sales tax. When privatization forces workers to accept poverty-level wages, their economic loss is felt through reduced sales for business, reduced tax receipts for government, and increased costs for public support services such as social assistance payments.

Privatizing and contracting out the work of government employees will do nothing to improve Saskatchewan’s economy. Public sector employment is a bulwark of stable, decent-paying work that can offset the downturn in the resource sector by providing a continued revenue stream for local businesses and local governments. The best course of action for the province’s economy is to maintain or even increase public sector employment levels – a move that would benefit Saskatchewan as a whole, rather than a select few out-of-province corporations.

3.) Increase social investment, and realize greater savings in other areas of government.

As the extent of Saskatchewan’s financial trouble became apparent, some of the first government services targeted for cutbacks were those that support the vulnerable and disadvantaged.

In the 2016-17 budget, funding was cut for the Buffalo Narrows Community Correctional Centre, a low-security facility that helped offenders find work and reintegrate into the community. Soon after the budget came more funding cuts: to the Northern Teacher Education Program, which supports and educates northerners seeking to become teachers in local communities; to the SAID program, which provides funding to support disabled citizens; and to the Lighthouse, a Saskatoon homeless shelter, among others.

These cuts come on top of longstanding resource shortages in other government- funded agencies that support the disadvantaged. Understaffing in the Ministry of Social Services has created enormous difficulty in effectively delivering income support and child protection services. Community-based organizations (CBOs) that support people living with disabilities and other vulnerable groups are perpetually short of funding. A chronic shortage of space in correctional facilities has meant rehabilitation programs are cancelled, as classrooms and gymnasiums are turned into makeshift dormitories.

While each service cutback reduces government expenditure by a small amount, they are unlikely to deliver savings in anything but the extremely short term. The same applies to chronic under-resourcing of support agencies like the CBOs and the Ministry of Social Services – while it may help keep individual Ministry budgets low, the service gaps it creates cause problems that government will ultimately be on the hook to address by other means.

The effects of this refusal to invest in the disadvantaged and vulnerable are apparent throughout Saskatchewan. Homeless individuals – who are denied access to shelters that no longer have the funding to accommodate them – instead spend their nights in police holding cells or end up in emergency rooms suffering from the effects of exposure to harsh weather. Lacking access to any meaningful rehabilitation programs, inmates who have completed their sentences quickly re-offend and return to the correctional system. In the North, poverty and a sense of hopelessness are exacerbated by a shortage of local teachers to serve as role models in elementary and secondary schools, and by a lack of higher education opportunities for those who do graduate.

The bottom line is that there is no financial logic in cutting funding for services that support those most in need of support. Disadvantaged and vulnerable individuals will eventually present a cost to government in some fashion – the only questions are what the extent of that cost is, and what form it comes in. If government wants to limit the costs of medical treatments, legal proceedings, and incarceration, then it needs to commit to funding supports that help people avoid contact with the medical, legal, and correctional systems – such as education, inmate rehabilitation, support payments subsidized housing, or assistance finding employment.

Taken as a whole, the costs of preventing harm are inevitably lower than attempting to address harm after the fact. The Saskatchewan government needs to accept this fact, and adjust its budgetary decisions accordingly – by increasing, rather than cutting, funding for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged people in our province, and realizing savings in other, costlier, areas of government.

NOTES

[1] Calculated from the government’s answers to Written Question 585 from the 4th Session, 27th Legislature. The increase in consultants spending has been calculated multiple times, with some variation in the results. The Provincial Auditor, using data from the government’s MIDAS database, calculated an increase of 228% between 2008-09 and 2013-14. The Saskatchewan NDP, also using figures from Written Question 585, arrived at an increase of 303% from 2007-08 to 2014-15. The consensus seems to be that expenditure on consultants has doubled or tripled under the Saskatchewan Party government’s term in office.

[2] Joe Couture, “Highways work goes private; Will lead to Regina, Saskatoon lab closures.” Regina Leader-Post, p. A1, April 11 2012; “Simon Enoch, “The Wrong Track: A Decade of Privatization in Saskatchewan.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, March 2015, p. 16.

[3] These comparisons use the “fully-burdened” cost public employees, which factors in benefit and pension costs, etc., as well as wage costs. See: Taylor Bendig, “Road to Ruin: Use of costly highways consultants has skyrocketed.” Behind the Numbers, March 17, 2015.

[4] “New report ‘final straw’ for Lean, Sask. NDP says.” CBC News, Feb. 1, 2016.

[5] “Backgrounder on K-Bro Linen Systems: The new provider of hospital linens in Saskatchewan.” Canadian Union of Public Employees, Dec. 17, 2013, pp. 3-4.

[6] Hugh Grant, Manish Pandey and James Townsend. Long-term Gain, Long-term Pain: The Privatization of Hospital Laundry Services in Saskatchewan. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, December 2014, p.5.

[7] Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan Hansard for Nov. 22, 2016, p. 1442

[8] The federal government’s Job Bank, which uses Statistics Canada data to provide wage information by community, lists “low” wages for janitors at $11.00 per hour in Regina and Saskatoon, and at the minimum wage of $10.72 in smaller centres such as Prince Albert and Melfort.